On this overview page you will find a short definition of bi + sexuality, the bi + sexual pride flag and what it means, a detailed article on bi + sexuality by Robin and further links and books on the subject. If you have any questions, write us a message – e.g. via our anonymous suggestion box .

Table of Contents

Brief definition

| Bi + sexual, B + isexuality / bisexual, bisexuality: A bisexual person feels romantically and / or sexually attracted to people of two or more genders. However, definitions of bisexuality are very diverse and controversial. The ‘+’ expresses these different definitions and shows that bi + sexual people can be attracted to people of several, many or all genders. |

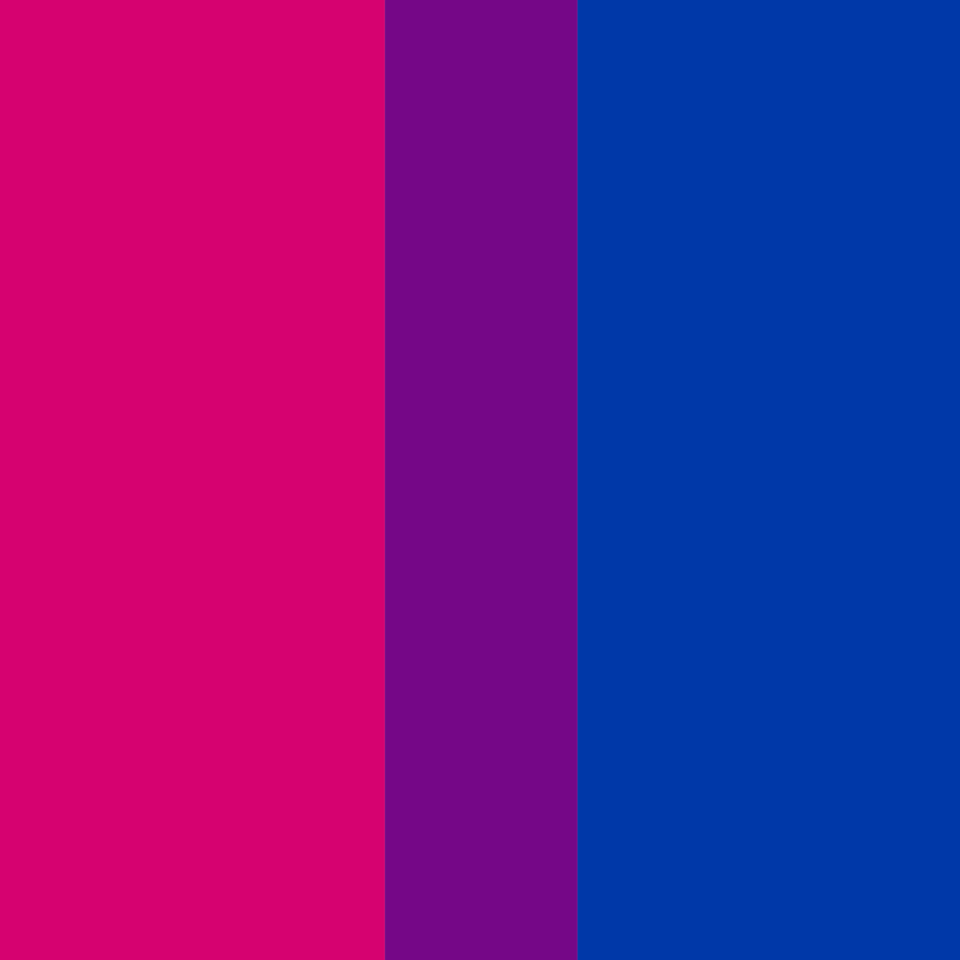

Pride Bisexual flag

[The picture shows the Pride Bisexual Flag for bisexual people. It consists of three horizontal stripes, the top and bottom being significantly larger than the middle. The colors from top to bottom: pink, purple and blue.]

The Pride Bisexual Flag for bisexual people was designed by Michael Page in 1988. He wanted to give the bisexual community its own symbol and increase the visibility of bisexual people in the queer community and society. The pink stripe stands for same-sex love, the blue for love for the opposite sex and the purple stripe in the middle stands for love for a person, regardless of where they are on the gender spectrum. [Source: http: // www. symbols.com/symbol/bisexual-pride-flag ]

What is bi + sexuality?

Robin wrote this article. We would like to revise and simplify the article soon so that everyone can understand it. Robin writes “woman *” and “man *” with a (*) – we don’t do that, but we have adopted Robin’s spelling. We thank Robin for the good cooperation!

Bi + sexuality, as a sexual orientation, includes the emotional, romantic and sexual attraction to more than one gender (BiNe – Bisexual Network e.V., nd). Bi + sexuality is characterized on the one hand by invisibility or a lack of representation and on the other hand the target of various forms of discrimination and antiquated stereotyping. Bisexuality must always prove itself in order to be recognized as an independent, equal sexual orientation such as homosexuality and heterosexuality. On the one hand, it is declared as a phase that must be followed by a clear categorization of homo- or heterosexuality. On the other hand, the psychoanalytic construction that all people are bi + sexual, an independent or independent identification option is taken, since bisexuality is considered implied. The initial terminological vagueness, the political and historical oblivion that followed and the academic and especially queer ignorance of bisexuality led to the invisibility of that sexual orientation.

The definition of bisexuality depends on the historical orientation and academic discipline and is correlated with the prevailing identity politics and political activism. Malcolm Bowie (1992) summarized three main strands of a definition of bisexuality. Accordingly, bi + sexuality represents, on the one hand, a coexistence of the incorporated binary gender order within the individual. On the other hand, the term was used as a synonym for ‘ hermaphroditisms’ used. The third strand of definition that has become the most widely accepted is the meaning of Bi + sexuality as a sexual orientation, which describes the romantic, sexual and emotional attraction to both women and men (Hemmings, 2002, p. 22) . The prefix “Bi” has three theoretical connotations: 1) the biological or anatomical meaning of femininity and masculinity (sex); 2) the psychologically female and male identity (gender); and 3) the intersection of homosexuality and heterosexuality as a third binary (sexual desire) (Storr, 1999, p. 3).

The history of the study of bisexuality begins with the scientific fields of psychiatry, psychoanalysis and sexology. In the 19th century Richard von Krafft-Ebing and later Havelock Ellis defined bi + sexuality as sexual dimorphism. The pathologization of bi + sexuality was continued by Sigmund Freud, who categorized bi + sexuality as “[in] stable sexuality in healthy, mature adults” (Pennington, 2009, p. 70). Basically, Freud defined bi + sexuality as ‘the mere development phase in childhood’. Alfred Kinsey generally characterized sexuality in the 1940s and 50s as something fluid and sketched bi + sexuality as a dual attraction to both sexes (Pennington, 2009, p. 71). Bi + sexuality as part of the Kinsey study was an integral part of subsequent developments,

During the 1970s a bi + sexual identity and politics were established based on political movements for lesbian and gay interests as well as feminist goals. Their rigid identity politics led to the dissatisfaction of many bi + sexual people, as the majority did not feel represented by the political and activist movements or generally felt included. The basic tenor of the negative debates was the lack of acceptance of bi + sexuality as a ‘ real ‘ queer identity, which resulted in a constant change between inclusion and exclusion of bi + sexual life plans in the queer community (Callis, 2009, p. 217). The eventuality of heterosexual passingfor bi + sexual people was a reason for excluding bi + sexual realities from the queer community. These developments are part of the “sex wars” (cf. Gayle Rubin, 1984). Sexual diversity was not tolerated by radical feminist movements in particular, as there was a general mistrust of women who identified themselves as bi + sexually. Such a ‘ kind’Contact with men led to women being discredited as feminists (cf. Jagose, 1996). The result was bisexual discrimination experiences in heterosexual, homosexual and feminist circles. Bi + sexual men in particular were declared a source of danger during the AIDS crisis, as they were assigned a kind of bridging function between homosexual and heterosexual groups of people. Although this relationship has proven to be wrong, bi + sexual people still cling to a large number of negative stereotypes and prejudices as a result.

Previous literature on bi + sexuality analyzes stereotypes and resentments against bi + sexual persons, such as characterization as promiscuous, sexually deviant, hypersexual, sexually adventurous and / or polyamorous (Callis, 2014, p. 67). Because of this stigmatization, bi + sexual people are increasingly using other labels or categories for their sexual orientation, e.g. pansexual, queer or polysexual (Klesse, 2011). Even if they personally identify as bi + sexual, they do not come out in order to avoid discrimination and exclusion (Pennington, 2009, p. 71). Corresponding forms of discrimination are assigned to biphobia, binegativity or monosexism. Monosexism describes the discrimination against people who have the emotional, to live romantic and sexual attraction to more than one gender (Bi radical, 2011). The main problem is the invisibility of bisexuality in society, in the media and in the scientific disciplinesBi Visibility Day or Celebrate Bisexuality Day, which takes place annually on September 23, is to promote greater visibility, acceptance and tolerance for bi + sexuality (GLADDD, 2016).

Literature and sources:

- Bi radical (2011). The monosexual privilege checklist. Accessed on October 10, 2018. Available from: https://radicalbi.wordpress.com/2011/07/28/the-monosexual-privilege-checklist/

- BiNe – Bisexual Network e. V. (nd). On 9/23 is international day of bisexuality (Bi-Visibility-Day). Accessed on 10/10/2018. Available at: https://www.bine.net/sites/default/files/arbeitsblatt_1_-_tag_der_bisexualitaet_ab_kl_9.pdf?language=de

- Bowie, Malcolm (1992). Bisexuality. In E. Wright (Ed.), Feminism and Psychoanalysis: A Critical Dictionary (p. 26). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Callis, April (2009). “Playing with Butler and Foucault: Bisexuality and Queer Theory.” In Journal of Bisexuality , 9 (3-4), pp. 213-233.

- Callis, April (2014). “Bisexual, pansexual, queer: Non-binary identities and the sexual borderlands.” In Sexualities , 17 (1/2), pp. 63-80.

- GLADDD (2016). #BiWeek 2016: Celebrate Bisexuality . Accessed on March 8, 2017. Available at: http://www.glaad.org/action/celebrate-bisexuality-biweek-2016

- Hemmings, Clare (2002). Bisexual Spaces: A Geography of Sexuality and Gender . New York & London: Routledge.

- Jagose, Annemarie (1996). Queer theory . Carlton, Vic .: Melbourne University Press.

- Klesse, Christian (2011). Shady Characters, Untrustworthy Partners, and Promiscuous Sluts: Creating Bisexual Intimacies in the Face of Heteronormativity and Biphobia. Journal of Bisexuality , No. 11, pp. 227-244.

- Pennington, Suzanne (2009). “Bisexuality.” In J. O’Brien (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Gender and Society (pp. 69-72). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Storr, Merl (1999). Bisexuality: A critical reader . London & New York: Routledge.

Your questions about bi + sexuality:

As far as I know, omnisexual people can already have preferences, which is the difference to pansexuality … Omnisexual people “see” the genders of other people and can also have “preferences”. Pansexual people are quasi “gender blind” and really only fall in love with people, regardless of their gender!

Thanks for the hint! Concepts are never 100% fixed and can be interpreted differently from community to community and from person to person. We find that the terms ‘omnisexual’ and ‘pansexual’ can mean the same thing – both pan- and omnisexual people can be attracted to people of all genders, and both pan- and omnisexual people can have preferences, or e.g. attraction feel differently towards different sexes. That is our experience and opinion on these terms, but it is not universally valid for everyone. Ultimately, all omni and pansexual people and communities have to decide for themselves how they want to define the terms for themselves.